To some a deity or a deity's messanger, to some a national bird and even a currency, to others a source of wonder,

the Resplendent Quetzal needs no introduction. Quetzals are a grouping

of 6 species in two genera within the trogon family (Trogonidae): Eared

Quetzal, Pavonine Quetzal, Golden-headed Quetzal, White-tipped Quetzal,

Crested Quetzal and Resplendent Quetzal. Resplendent Quetzal is the only

Mesoamerican quetzal species, with Eared

Quetzal being North American and the others being South American.

Resplendent Quetzal is by far the most famous for the male’s enormous

tail that can be >75cm in length (this photo is of the costaricensis

subspecies that has a slightly shorter tail than the nominate… believe

it or not!). The funky head feathers and sickle-shaped wing coverts set

against the waxy red belly add to the splendour. Resplendent Quetzal is

not the only species in the world with a long tail but it is rather

unique… Can you spot what is so unusual about the tail? Click on the photo to enlarge.

If you cannot figure out what is special about the tail in the above photo, this second photo may help:

If you still need help, notice how the tail feathers are black and normal length (the undertail coverts are white) and the long streamers fall over top of them. In short, it

is NOT the tail feathers proper (the rectrices)

but rather the uppertail coverts that are elongated. Many birds

have long tails derived from elongated tail feathers

but having elongated uppertail coverts to this extent is highly

unusual. Coverts form the function of “covering” and creating the smooth

surface so important for streamlining. Uppertail coverts cover the base

of the tail so that the tail is more aerodynamic. Having a covert

longer that the feathers it is supposed to be covering is quite unusual.

There

are four elongated uppertail coverts: two that are long and two that

are extremely long!

Saturday, January 30, 2016

Sunday, January 24, 2016

Owls of Costa Rica

On a recent trip to

Costa Rica I saw 13 species of owl. This blog pot discusses those species that

I managed to get good photos of, which is most of the country’s owls.

Bare-shanked

Screech- Owl (Megascops clarkii), reddish-brown morph

The Bare-shanked Screech-Owl is endemic to

the mountains of Costa Rica, Panama and extreme northwestern Colombia (from

approx.. 900m – 3200m ASL but usually more common in the mid elevation cloud

forest and humid forest). The first photo shows the bare shanks that gives the

species its name. The second photo shows the wing droop display posture when

delivering the territorial song. This is a red morph individual, which seemed

more common in the parts of Costa Rica I visited than the dark brown morph.

Pacific

Screech-Owl (Megascops cooperi)

The Pacific Screech-Owl occurs in a

relatively narrow strip along the Pacific coast from southwestern Mexico

(Oaxaca and Chiapas) to northwestern Costa Rica (mostly Guanacaste). This is a

resident of dry forest types (also mangroves in some contexts), mostly in the

lowlands but sometimes as high as 1000m ASL, although this individual

photographed by Adrian Arroyo and myself in Monteverde, Costa Rica is at

roughly 1300m ASL. Although common in its limited range, this is a poorly known

species. This is one of the few species of Megascops

that is not known to have a red morph (this follows the general pattern of

higher prevalence of red morph birds in humid environments).

Vermiculated

Screech-Owl

complex in Costa Rica

Four photos

showing:

* (Megascops vermiculatus), brown morph,

Monteverde, Costa Rica,

* (Megascops guatemalae or vermiculatus), reddish-brown morph, Boca

Tapada, Costa Rica.

It is worth stating

firstly that there is little agreement on the species status of the various

taxa within the Vermiculated Screech-Owl complex. Though some only recognise

one or two species, others such as the IOC treat this group as five distinct

species as follows:

* Middle American

Screech-Owl (Megascops guatemalae)

* Vermiculated

Screech-Owl (Megascops vermiculatus)

* Roraiman

Screech-Owl (Megascops roraimae)

* Napo Screech-Owl

(Megascops napensis)

* Choco Screech-Owl

(Megascops centralis)

With the help of

Adrian Mendez and Adrian Arroyo, I photographed this brown individual (first

two photos) in Monteverde on the Pacific slope at approximately 1300 m ASL. I

photographed this reddish-brown individual (third and fourth photos) near Boca

Tapada in the Caribbean lowlands in the extreme north of the country. The issue

for me was that the bird in Monteverde gave what I consider to be a typical

song for M. vermiculatus, i.e. a very

rapid trill that lasted approx. 8 seconds, whereas the bird I heard in Boca

Tapada gave a very long trill that I timed at 20 seconds in duration and which

struck me as more akin to M. guatemalae.

Based on song along, I was inclined to think that two different species are

present in Costa Rica (based on the split of the M. guatemalae complex into multiple species).

Nonetheless, the

appearance of these birds did not match my expectations based on call. The bird

from Monteverde, as you can see in these photos, is well marked with:

* a well-defined

facial disk (suggests guatemalae

according to the literature)

* prominent black

streaking and cross barring below but not so strongly “vermiculated” (suggests guatemalae)

* prominent

blackish crown streaks (may suggest guatemalae)

* weakly marked

eyebrows (suggests vermiculatus)

* pale, somewhat

greenish bill

The bird from Boca

Tapada shows:

* a relatively

weakly-defined facial disk (suggests vermiculatus)

* finely

vermiculated underparts with little to no black markings (suggests vermiculatus)

* relatively

prominent blackish crown streaks (may suggest guatemalae)

* weakly marked

eyebrows (may suggests vermiculatus

but not clear if relevant in this morph)

* pale,

horn-coloured bill

The physical

features of these birds therefore leave me with some doubts. Of course, the

morphs are not the same so direct comparison is not really possible. In the end

though, the long song of the bird in the Caribbean lowlands versus the short

song of the bird on the Pacific slope suggests to me that the status of the

screech-owls in Costa Rica warrants further investigation and clarification.

This is something that some budding Costa Rican birders and ornithologists

might like to investigate!

Crested

Owl (Lophostrix cristata), pair at day

roost

The unique

(monotypic genus) and spectacular Crested

Owl is always a special treat to observe. In this case, special thanks go

to Jose (Cope) Arte who found this roosting pair of Crested Owls in the Caribbean lowlands of Costa Rica. You will

notice that one of these owls has a cataract in one eye, although that does not

seem to have weakened the pair bond between these two. Although it is very hard

to tell in this particular photo, when observed from two angles, I felt the owl

with the cataract was very slightly larger and hence probably female. The Crested Owl is a widespread, mostly

lowland rainforest species, though sometimes found as high as 2,000 m ASL. The

subspecies found in Central America is L. c. stricklandi. The slight colour

difference between the pair was interesting and when I compare these

individuals to Crested Owls I have

seen in Mexico (click left arrow) they don’t seem to be quite as reddish in the

face. The Central American birds are much darker than birds from Ecuador and

Peru. Some have argued that may warrant a future split since the distribution

is disjunct, with the Amazonian population being separated geographically from the

Central America and northwestern (Pacific) South American birds.

Spectacled

Owl (Pulsatrix

perspicillata)

With thanks again

to Cope Arte, I was delighted to get a chance to see this pair of Spectacled Owls on a day roost.

Spectacled Owl is the largest (can reach 52 cm in length) and most widespread member

of the genus Pulsatrix. This genus is confined to the Neotropics and has only

three species (some authors split Spectacled Owl into two species, giving rise

to a fourth species, but this is not widely accepted). The first photo is a crop showing one more closely to reveal

the exceptionally beautiful pattern and and the second photo shows the

pair together.

Black-and-white

Owl (Strix nigrolineata)

* Taxonomic note:

some authors place this species in the genus Ciccaba

The Black-and-white Owl is one of two

Neotropical species with a unique jet black on white plumage, offset by yellow

bare part colouration (possibly a third species exists, the San Isidro mystery

owl). Black-and-white Owl is found

in Central America (south from southernmost Mexico) and long the Pacific coast

of northern South America (as far south as extreme northern Peru) and east

across northernmost Venezuela. This is a large owl (females can measure as much

as 40 cm in length) with a distinct guttural song. Despite their large size

they seem to consume a lot of invertebrates. This bird came around the lights

of the Laguna Lagarto lodge at night, seemingly looking for moths and perhaps

also bats. Mikkola (2014) states that Black-and-white Owl and Black-banded Owl

“clearly overlap in range in Colombia”; however, examination of range maps from

a variety of sources suggests this is not the case.

Mottled

Owl is a

widespread species (unless you accept the proposed split of the Central

American taxon) that occupies a wide variety of habitats and a considerable

altitudinal range; for example I heard one at approximately 2400 m ASL on

Volcán Irazú. I have found it to be very common in many parts of the

Neotropics, with the possible exception of the Atlantic rainforests of Brazil,

where a disjunct population occurs that seems more thinly distributed. This

bird is more buffy below than others I have photographed in Mexico (possibly a

question of colour morph).

Costa

Rican Pygmy-Owl

(Glaucidium costaricanum), brown and red morphs

The Costa Rican Pygmy-Owl is endemic to the

mountains of Costa Rica and western Panama (rarely as low as 900m ASL but

usually from ~1200 – 3400m ASL). For the most direct comparison I combined two

photos into a collage showing the two colour morphs, red and brown. As

discussed previously (see my previous post on polychromatism), colour morphs

are common in the pygmy-owls (genus Glaucidum)

and this species has two morphs. This taxon is now widely considered to be a

full species; although it was formerly considered to be a subspecies of Andean

Pygmy-Owl (genetic analysis suggests it is more closely related to Mountain

Pygmy-Owl).

Ferruginous

Pygmy-Owl (Glaucidium brasilianum), brown and red morphs

*Taxonomic note:

some authors treat this taxon as Ridgway’s Wood-Owl (Glaucidium ridgwayi)

The Ferruginous

Pygmy-Owl is one of the most widespread of the Pygmy-owls (at least in the

broadest sense as currently recognised by the IOC). In Costa Rica this species

only occurs in the dry northwestern part of the country. This individual was

photographed at Palo Verde in the early morning.

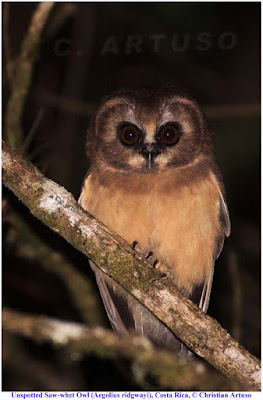

Unspotted

Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius ridgwayi),

Costa Rica

An avian enigma

that is rarely seen, the Unspotted Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius ridgwayi) is a close relative of the Northern Saw-whet Owl

and they have in the past been considered conspecific by some. I was absolutely

delighted to spot the unspotted perched quietly in some liana vines beside a

small road at approximately at 2400 m above sea level near Los Quetzales

National Park, Costa Rica after working hard to try to hear one. Even better, I

got to share my find with some ecstatic Costa Rican birders a couple of days

later. Some taxonomists consider this to be the nominate subspecies, although

others consider this species to be monotypic.

Unspotted

Saw-whet Owl is

the only extant species in the genus Aegolius

from Mesoamerica. In addition there is one species from South America

(Buff-fronted Owl) and two from North America (the Northern Saw-whet Owl and

the Boreal Owl, which in addition to North America also occurs across northern

Eurasia). An additional Caribbean species, the Bermuda Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius gradyi) is now considered

extinct.

One of things I

find most fascinating about the Unspottted

Saw-whet Owl is that their adult plumage is extremely similar to the

juvenal plumage of Northern Saw-whet Owl. Although there are many closely

related bird species pairs where juvenal plumages or female plumages are very

similar, and of course some where all adult plumages are similar, this seems

like a rare case in the avian world where a species’ adult plumage closely

resembles the distinct juvenal plumage of congenitors (making them rather Peter

Pan-like in appearance, i.e. they give the impression of having never grown

up). There are cases of individual birds from different taxa breeding in

juvenal or subadult plumages but the evolutionary mechanism involved in this

case remains unclear.

Thank you!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)